Travel

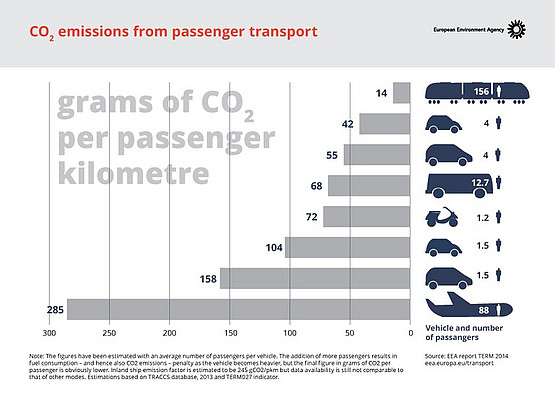

This figure from the European Environment Agency compares greenhouse gas emissions per person for different modes of transport; see also Wikipedia.

Climate change

There is scientific consensus not only about the reality of anthropogenic global warming and the urgent need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in all areas, but also about other existential threats to humanity and the urgent need to respond appropriately to each one (Ripple et al., 2017).

The global mean temperature in 2016 was 1.1°C above the pre-industrial level, breaking the previous record from 2015 (World Meteorological Organisation, 2017). Changing temperature and precipitation patterns will affect most human social and economic activities (mobility, trade, tourism, etc.), triggering regional conflicts, (forced) migration and increased mortality rates, especially for social classes that are less able to adapt for financial or health reasons (Field et al, 2014; Zhengelis, 2015). Proximate causes will include extreme weather events (posing serious risks to humans, ecosystems and endangered species), rising seas, salination of agricultural soils, more frequent or intense heat waves (wet-bulb temperatures approaching body temperature), longer droughts, deglaciation affecting water supplies, expanding deserts, forest dieback, more frequent or unprecedented forest fires or flooding, ocean acidification, and accelerated loss of biodiversity (species extinction) on both land and sea. Developments of this kind may interact with each other (e.g., ecological cascade effects), and climate forcing mechanisms may self-reinforce (positive climate change feedback), leading to "runaway" warming. Long-term extrapolations and order-of-magnitude estimates suggest that the past, present and future emissions of a billion people in richer countries could eventually cause the premature deaths of a billion future people in poorer countries (cf. Nolt, 2011).

Although most countries agreed to limit the temperature increase to 2°C in the landmark 2015 Paris agreement, the agreement is inadequate in several respects (Savareis, 2016). The nationally determined contributions are not legally binding (Bodansky, 2016). From a global political and economic viewpoint, the forces against the agreement may still be greater than those for it (Falkner, 2016).

Meanwhile, global emissions are still increasing and 2018 set a new record (International Energy Agency, 2019). The latest increases reflected a "healthy" global economy and increased heating and cooling in response to extreme temperatures caused by climate change. The latter is a kind of feedback loop, comparable with Albedo, forest fires, and melting permafrost. These are clear signals that global warming is an unprecedented, existential global emergency.

The role of individual carbon footprints

Currently, the average person in the world emits about 5 tonnes CO2 equivalent per year; the U.S. average is 20 tonnes (more). A sustainable carbon footprint is 2 to 3 tonnes per person per year -- equivalent to attending just one conference per year on a different continent. The ocean CO2 sink is currently about 2 GtC/yr; the terrestrial CO2 sink is about 3 GtC/yr, total 5 GtC/yr (more). The equivalent CO2 value is 3.7 times greater, and dividing that by 7 billion people yields the individual value. But even without flying or driving, the average person in a rich country cannot avoid creating this much CO2 -- merely by living in a well-insulated flat with a minimum of heating in the winter, eating regular vegan food, and using public transport. Moreover, this is true regardless of how the political situation develops in coming years -- whether governments assert their power over corporations, or flying is taxed, or oil exploration is universally banned.

It follows that individuals will have to drastically reduce their carbon footprints -- no matter what happens (Parncutt, & Seither-Preisler, 2019). This applies to academics the same as it applies to anyone else. Before continuing, it is important to recognize what kind of statement this is. It is merely a logical conclusion based on clear evidence. In that sense, it is a fact. It is not a political demand, nor is it a moral plea.

The role of aviation and academic conferences

Aviation is one of several ways in which richer countries are causing long-term environmental destruction that will be felt most acutely in poorer countries -- an example of north-south injustice (Anand, 2017; Goodman, 2009). Aviation is now responsible for about 3% of global CO2 emissions, having grown by 5% per year from 2% a decade ago. Air travel is also becoming more fuel-efficient, at between 1% and 2% per year. Biofuels are not a reasonable alternative as long as they could indirectly cause rainforest destruction or aggravate existing global hunger (Charles et al., 2007). Other greenhouse gas emissions and additional factors such the elevation at which emissions occur, the different atmospheric lifetimes of GHGs in the atmosphere, and complex interactions between different GHGs mean that the contribution of aviation to global warming is now roughly 5%. Roughly 5% is also the proportion of people in the world who have every flown (Goezte, 2019; Negroni, 2016). If everyone in the world flew like the top 5%, global emissions would roughly double.

When all GHGs and their different effects are considered, the contribution of one economy-class seat on a long-haul intercontinental return flight is comparable with driving a car to and from work for a whole year (calculate flight emissions here) or eating meat for five years (1 kg/week). All three cases are equivalent to burning roughly one tonne of carbon or emitting roughly 3.7 tonnes of CO2.

That "conference tourism" is environmentally problematic has been clear for a long time (Høyer & Næss, 2001). A case study of a typical science PhD student (Achten et al., 2013) found that mobility represented 75% of emissions (of which conference attendance 35%) and infrastructure 20%. Video conferencing could have reduced emissions by 44%. Flying may represent between 20% and 50% of all emissions produced by a university, depending on location and research focus. Flying from one conference to another on different continents may be an example of "binge flying" (cf. Cohen, et al., 2011). But individual academic careers may benefit more from staying home and writing journal articles.

Clearly, the easiest and most effective way for a typical researcher (middle-class lifestyle, rich country) to significantly and immediately reduce their individual carbon footprint is to reduce the distance flown per year or avoid flying altogether (Anglaret et al., 2019). The other main options are eating less meat, driving less, and having fewer children (Wynes & Nicholas, 2017). Remarkably, frequency of air travel is not correlated with general environmental awareness (Kroesen, 2013), suggesting that even the environmentally aware are either uninformed about these quantitative relationships or susceptible to denial.

If our aim is to create a "sustainable" conference culture, in which academics can still fly to international conferences 50 or 100 years from now, we need to pro-actively prevent a global climate crisis that would turn global academic conferences into unaffordable luxuries. If the carbon budget was distributed proportionally across sectors, the aviation sector would have to reduce emissions by 14% per year to achieve the Paris 1.5°C target. We must therefore urgently consider and combine different strategies for reducing global greenhouse emissions (including, but not confined to, those of the aviation industry), such as carbon taxes, bans on advertising that directly promotes fossil fuel or meat consumption, bans on airport expansion (no new runways), and investment in environmentally friendly high-speed trains and intercontinental shipping - in addition to more specific strategies such as semi-virtual conferences. For strategies of this kind to work, diverse forms of global political negotiation will be necessary, in which academics could play a central role.

ICMPC15/ESCOM10

One option is to go fully virtual, asking all participants to record their talks, watch other talks on the conference website, and contribute to online discussions (more). For ICMPC15/ESCOM10, preferred a semi-virtual format with more personal contact, in which the amount of flying per person decreases as the number of global hubs increases (Parncutt et al., 2019).

Coroama, Hilty and Birtel (2012) estimated that a multi-hub, semi-virtual conference could reduce travel-related greenhouse gas emissions by 37% to 50% relative to an equivalent single-location conference. At ICMPC15/ESCOM10 we aimed to halve carbon emissions per participant.

Additional advantages of ICMPC15's multi-location format are:

- Travel costs will be reduced for the average participant, and hence for universities that fund conference travel.

- Inclusion in the program will depend more on academic quality and less on financial resources.

- The number of participants will increase, as will their cultural diversity. Opportunities for meeting possible future collaborators with specific backgrounds, skills or motivations will improve.

- Passive or active participation will become easier for colleagues with reduced mobility.

- The conference will be more global in character.

In future, it may be possible to reduce emissions by 90% -- while at the same time further improving accessibility, inclusiveness, and cultural diversity -- by increasing the number of hubs so almost everyone can attend without flying.

Participants are asked to travel to the nearest hub and avoid or reduce flying if reasonably possible. Participants who do fly may consider reducing the number of take-offs, replacing part of their journey with surface transport, or combining the trip with a holiday to reduce average daily emissions. Another option is to consider yearly personal emissions and reduce the total in other ways. We also ask conference participants to sign the #flyless petition.

Working on a laptop is easier on a train than a plane, and night trains can be convenient. Time and money can be saved by avoiding trips to and from airports, early check-ins, security checks, and baggage carousels. Sometimes both conference and holiday travel can be included in the same discount train or bus pass. Options of this kind are entirely voluntary and play no role in abstract review or program construction.

Notes

This text was written by Richard Parncutt in collaboration with Jakob Mayer, Wegener Centre for Climate and Global Change, Graz. Feedback is welcome. The issues will be discussed in evaluation and closing sessions. ICMPC15/ESCOM10 supports the academic Flying Less initiative.

References

Achten, W. M., Almeida, J., & Muys, B. (2013). Carbon footprint of science: More than flying. Ecological indicators, 34, 352-355.

Anand, R. (2017). International environmental justice: A North-South dimension. Routledge.

Anglaret, X., Wymant, C., & Jean, K. (2019). Researchers, set an example: fly less. Conversation, February 13.

Bodansky, D. (2016). The Paris climate change agreement: a new hope? American Journal of International Law, 110(2), 288-319.

Charles, M. B., Ryan, R., Ryan, N., & Oloruntoba, R. (2007). Public policy and biofuels: The way forward?. Energy Policy, 35(11), 5737-5746.

Cohen, S. A., Higham, J. E., & Cavaliere, C. T. (2011). Binge flying: Behavioural addiction and climate change. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(3), 1070-1089.

Coroama, V.C., Hilty, L.M., Birtel, M. 2012. Effects of Internet-based multiple-site conferences on greenhouse gas emissions. Telematics and Informatics, 29, 4, 362-374.

Falkner, R. (2016). The Paris Agreement and the new logic of international climate politics. International Affairs, 92(5), 1107-1125. full text

Field, C.B. et al. (Eds.) (2014). IPCC Summary for policymakers. In Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects (pp. 1-32). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gerhards, J. (2019). “Greetings from Berlin, Tokyo, Beijing” – Should we call time on international academic travel? LSE Impact Blog, blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences

Goetze, S. (2019). Hört endlich auf zu fliegen! Der Freitag, freitag.de.

Goodman, J. (2009). From global justice to climate justice? Justice ecologism in an era of global warming. New Political Science, 31(4), 499-514.

Høyer, K. G., & Næss, P. (2001). Conference tourism: A problem for the environment, as well as for research?. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 9(6), 451-470.

International Energy Agency (2019). Global Energy & CO2 Status Report: The latest trends in energy and emissions in 2018. iea.org/geco.

Kroesen, M. (2013). Exploring people's viewpoints on air travel and climate change: Understanding inconsistencies. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(2), 271-290.

Negroni, C. (2016). How much of the world’s population has flown in an airplane? Some numbers, and some guesses. Daily Planet, airspacemag.com/daily-planet.

Nolt, J. (2011). How harmful are the average American's greenhouse gas emissions? Ethics, Policy and Environment, 14(1), 3-10. full text

Parncutt, R., & Seither-Preisler, A. (2019). Live streaming at international academic conferences: Ethical considerations. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene, 7, 55. full text

Parncutt, R., Meyer-Kahlen, N., & Sattmann, S. (2019). Live-streaming at international academic conferences: Technical and organizational options for single- and multiple-location formats. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene, 7, 51. full text

Ripple, W. J., Wolf, C., Newsome, T. M., et al. (2017). World scientists’ warning to humanity: A second notice. BioScience, 67(12), 1026-1028. full text

Savaresi, A. (2016). The Paris Agreement: a new beginning?. Journal of Energy & Natural Resources Law, 34(1), 16-26. full text

Wynes, S., & Nicholas, K. A. (2017). The climate mitigation gap: Education and government recommendations miss the most effective individual actions. Environmental Research Letters, 12(7), 074024. full text

World Meteorological Organization (2017). Climate breaks multiple records in 2016, with global impacts. public.wmo.int/en/media/press-release/climate-breaks-multiple-records-2016-global-impacts [25.03.2017].

Zenghelis, D. (2015). Decarbonisation: Innovation and the economics of climate change. Political Quarterly, 86, 172–190.